Following on from last week's essay mixer, we'll both look back in history, and consult a popular online personality for a deeper introduction to internet-age institutions. In order to understand our roots, we turn to the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) and a governance document–“RFC 7282: On Consensus and Humming in the IETF”–they ratified in 2014. The document cites a presentation given by Dave Clark in 1992, just as the web was gaining momentum. It is our hope that, by gathering these obscure historical moments and ideas, we can seed diverse cultures of love, internet style.

How does this fit into Kernel?¶

Love is messy and unpredictable though, and often seems to be at odds with our very human desire for legibility. We want things to be at least roughly ordered and to "make sense". But this is not necessarily the way of the world. In fact, legible routines are often hallmarks of authoritarian structure, and so we need to find a middle way between the top-down imposition of one man's idea of order and the tyranny of structurelessness.

By combining insights from the two articles on which this brief is based, we hope to indicate how our own embodied being can give us the knowledge we need–as we need it–to navigate this particular set of complementary opposites constructively and, as always, with humility.

"It is easier to comprehend the whole by walking among the trees, absorbing the gestalt, and becoming a holographic/fractal part of the forest, than by hovering above it." - Venkatesh Rao

IETF governance revolves around the simple maxim that engineering is about trade-offs. As such, we need clear ways of thinking about how we make decisions. We ought to avoid simplistic "majority rule" and get to rough consensus decisions which promote the best technical outcomes.

"Consensus decision-making is typical of societies where there would be no way to compel a minority to agree with a majority decision [...]. If there is no way to compel those who find a majority decision distasteful to go along with it, then the last thing one would want to do is to hold a vote: a public contest which someone will be seen to lose. Voting would be the most likely means to guarantee humiliations, resentments, hatreds, in the end, the destruction of communities. What is seen as an elaborate and difficult process of finding consensus is, in fact, a long process of making sure no one walks away feeling that their views have been totally ignored.” - David Graeber

Rough consensus is therefore a sort of "exception processing", meant to deal with cases where the person objecting still feels strongly that their objection is valid and must be accommodated. In order to reach rough consensus, minority views must be addressed, with justification. Simply having a large majority of people agreeing to dismiss an objection is not enough; the group must have honestly considered the objection and fully addressed all technical issues.

In an article called “Rough Consensus and Maximal Interestingness”, Venkatesh Rao writes::

"Rough consensus is about finding the most fertile directions in which to proceed rather than uncovering constraints. Constraints in software tend to be relatively few and obvious. Possibilities, however, tend to be intimidatingly vast. Resisting limiting visions, finding the most fertile direction, and allying with the right people become the primary challenges."

Using a familiar thinking pattern, the IETF addresses these challenges in the negative. They consider issues first rather than agreements; address them but don’t necessarily accommodate them; and understand (through iterative practice) that consensus is a tool and not a destination.

Prompt: Consensus is a tool, not a goal. We should use it for what three primary tasks?

Resisting limiting visions, finding the most fertile directions, allying with the right people.

What follows is a condensation of the main points in the IETF’s RFC 7282:

1. Lack of disagreement is more important than agreement¶

- Coming to consensus is different from having consensus. In coming to consensus, the key is to separate those choices that are simply unappealing from those that are truly problematic.

- Closure is likely to be achieved more quickly by asking for objections rather than agreement.

1a. The two meanings of "compromise"¶

- When it comes to engineering choices, compromises are expected and essential. We must weigh trade-offs and collectively choose the set of trade-offs that best meets the full set of requirements.

- Among people, fcompromises are far less desirable. Such compromises occur most often when one group has given up and are trying to appease the others. Conceding when there is an outstanding technical objection is not coming to consensus. Even worse is horse-trading: "I object to your proposal for such-and-such reasons. You object to my proposal for this-and-that reason. If you stop objecting to my proposal, I'll stop objecting to your proposal and we'll put them both in."

Prompt: When determining social consensus, should we ask for agreement or objections?

Objections.

2. Issues are addressed, not necessarily accommodated¶

- "That's not my favorite solution, but I can live with it. We've made a reasonable choice" - this is consensus, not rough. It’s only rough when an unsatisfied person still has an open issue, but the group has truly answered the objection at a technical level.

- The final decision then relies on the good judgement of the consensus caller, or chair. Finding “rough consensus” means that not only has the working group taken the objection seriously, but that it has fully examined the ramifications of not accommodating it, and concluded that the outcome does not constitute a failure to meet the technical requirements of the work.

- What can't happen is that the chair bases their decision solely on hearing a large number of voices saying, "The objection isn't valid." That would simply be to take a vote. A valid justification needs to be made.

Prompt: Does rough consensus mean everyone is satisfied?

No, only that all technical objections have been answered.

3. Humming, not voting¶

- We don't vote because we can't vote. The IETF is not a membership organization, it's nearly impossible to figure out who would get a vote for any given question. There are only “participants”, not “members”.

- We do, on occasion, take informal polls to get a sense of the direction of the discussion, but we try not to treat a poll as a vote that decides the issue. Sometimes, to reinforce the notion that we're not voting, instead of a show of hands, we "hum".

- One reason for humming is pragmatic: to find a starting place for the conversation. A hum can indicate that there were less objections to A than to B at the beginning of the discussion, so starting with the objections to A might shorten the discussion.

- Another reason is to "take the temperature". A few loud hums for choice A and a larger number of non-committal hums for choice B might indicate that some believe there are serious problems with choice B, albeit the more popular by sheer number of people.

- To re-emphasise the major point: a show of hands might leave the impression that the number of people matters in some formal way. It doesn’t.

- The formulation and order of questions asked can have huge effects on the outcome. Asking, "Who supports going forward with this proposal?", and asking it first, can cause more people to hum in the affirmative than differently formulated questions, or asking the same question after some more "negatively" framed questions. Any sort of polling must aim to prompt discussion and questions, not conclude the matter.

Prompt: Do the number of votes, hums, or hands matter in consensus-based decision making?

No!

4. Consensus is the path, not the destination¶

- Consensus is a tool to ensure we get to the best technical outcomes.

- Experience has shown us that traditional voting leads to gaming of the system; "compromises" of the wrong sort; important minority views being ignored; and worse technical outcomes.

- Again, you cannot call consensus by counting people, it must be about the outstanding issues and whether they have been addressed.

4a. One hundred people for and five people against might not be rough consensus¶

- If a minority has a valid technical objection, that objection must be dealt with before consensus can be declared.

- It's the absence of an unaddressed open issue, not the number of people agreeing, which determines consensus. You may proceed in spite of issues that have been purposely dismissed, but not ones that have been ignored.

4b. Five people for and one hundred people against might be rough consensus¶

- This is the most controversial scenario. It generally occurs in the case of small, active working groups where an objector recruits many otherwise silent participants to their cause.

- The principle is still the same: if the objection has been addressed, and the new voices are not giving informed responses to that point, it can still justifiably be called rough consensus.

Prompt: The existence of what key factor, rather than number of people, determines consensus or its lack?

An unaddressed open issue.

Funded code running consensus¶

Most of this is still relevant 30 years later, and there are two points which remain critical for any system of technical governance:

Voting ought to be about finding useful starting places for generative discussion, not reaching conclusions; and

Sheer number of people or votes does not determine consensus.

What is problematic now is that consensus is "called" by a chair, which is a position of authority we cannot afford if we are to build truly decentralized systems. However, it's exactly the authority conferred by the formal position of "chair" which gives individuals the power to get work done once all technical objections have been addressed. So how are we to balance the lack of authority with our need to move forward along the most fertile paths?

The proposed solutions to this question generally take the form of some kind of distributed and dynamic reputation system, because reputation gives certain individuals the legitimacy required to shift conversations and social conventions. This is a necessary and salient point to acknowledge in the social protocols and culture which inform any system of technical governance. Where there are shadow hierarchies, there is abuse and inefficiency, and so individuals must be aware of the regard in which they are held within their chosen communities and respond accordingly. We state elsewhere that the idea for any kind of leader - read: host, or server - is to give away their importance without shirking responsibility.

However, we can perhaps turn to some economics for other sustainable and resilient solutions. The old idea is "running code and rough consensus". However, the code we now all run establishes consensus, and makes money (literally). So, rather than having a single chair who specifies which path is best to follow for the whole working group, why not have as many working groups as we can currently fund by means of our shared code? We can even program non-linear funding mechanisms which also act as on-chain economic signals of support - as we saw with EIP-1559 - in order to determine collectively the best technical outcomes.

In 1992, there were sufficiently few people and resources online that it made sense we all came to at least rough consensus. Forking the internet in the 90's was not an option. However, if our votes are simultaneously economic actions that fund a given project, then we can cultivate governance systems that determine what “valuable work” means and fund it simultaneously . Though it sounds great to "address all technical objections"–in practice–there are often so many variables at play that doing so in a credibly neutral manner is impossible. Cost, however, is a single variable we can all reason about to at least a first approximation.

Rough consensus is just "exception processing" for people. When your running code already establishes economic consensus, you can leverage this to fund multiple different working groups with multiple approaches, removing the need to handle exceptions at the initial stage because you know it will be decided by actual use later on. “Exceptions” in this context means only those proposals which do not adequately address valid technical concerns. There is the potential that certain proposals could be at odds with the culture and ethos of a given community, in which case lessons from political history–like defensive democracy–are fertile starting points for thinking about how to encode principles as a means of establishing credibly neutral incentive structures.

"In other words, true north in software is often the direction that combines ambiguity and evidence of fertility in the most alluring way: the direction of maximal interestingness."

Prompt: When running code already establishes economic consensus, do we need strong exception processing for people's technical objections such that we collectively explore only one option? Why?

No! Because votes are funds, so many different approaches can potentially be funded without addressing all technical objections in the preliminary stages.

Legibility¶

We tend to reject illegible systems that we can’t easily understand and opt for more orderly approaches. The IETF brief was written in response to this tendency, which arises from the anxiety produced by ambiguity or “rough” systems that aren’t always exactly predictable. And now, we're saying it's not even about rough consensus. It's about however many projects can garner sufficient support because, in open protocols for money, a "vote" is an economic signal which can simultaneously be used to fund what is being voted on.

If you're objecting to the inevitable chaos of such an approach, it's time to talk about legibility.

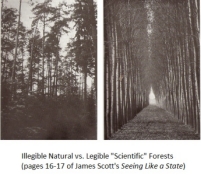

James Scott's book, Seeing Like A State, describes how modern states reorganized societies to make them more legible to the apparatus of governance. Venkatesh Rao summarises the book in his own article called “A Big Little Idea Called Legibility”:

""The state is not actually interested in the rich functional structure and complex behaviour of the very organic entities that it governs (and indeed, is part of, rather than “above”). It merely views them as resources that must be organised in order to yield optimal returns according to a centralized, narrow, and strictly utilitarian logic."

Importantly, this happens on both left and right: the failure mode is ideology-neutral: it arises from a flawed pattern of reasoning rather than values.

This style of thinking leads to simplification, since:

"a reality that serves many purposes presents itself as illegible to a vision informed by a singular purpose [...] The deep failure in thinking lies is the mistaken assumption that thriving, successful and functional realities must necessarily be legible."

Prompt: What kind of reasoning sees organic entities as resources to be organized in a legible way which yields uniformly high returns?

Flawed.

Don't misunderstand: there is - as always - a trade-off between "simple to understand" and "functionally useful", and there are some cases in which the first is genuinely useful. For instance:

"The bewilderingly illegible geography of time in the 18th century, while it served a lot of local purposes [...], would have made modern global infrastructure, from the railroads (the original driver for temporal discipline in the United States) to airlines and the Internet, impossible."

We can learn a great deal from the history of states and the very human desire for legibility. It does, in some instances, lead to improvement. For instance, we should learn from the IETF that:

Closure is more likely to be achieved quickly by asking for objections rather than agreement.

We should compromise between engineering choices, but not between people.

We must address issues and justify technical choices to the greatest extent possible.

Majority rule sucks.

We must use consensus as a tool, not an end.

We must build principled systems which cultivate our ability to make optimal collective choices.

That said, we no longer operate in a version of the internet where rough consensus about a single way forward is even possible, let alone desirable. We can choose to embrace the generative chaos and use economic code which establishes consensus to fund as many different approaches as is appropriate, without treating humans as exceptions to be handled.

"The high-modernist reformer does not acknowledge (and often genuinely does not understand) that he/she is engineering a shift in optima and power, with costs as well as benefits. Instead, the process is driven by a naive 'best for everybody' paternalism that genuinely intends to improve the lives of the people it affects."

Don't be a reformer. Build systems that help people govern themselves, and then - the most radical choice of all - let them actually do so.