nor fear the seeming.

Here is waking in the dreaming.

– Abraham Merritt (adapted)

Is it possible to guard effectively against the inertia of language? Arguably, we cannot achieve this in natural language, but might we be able to develop a "perfect language" in which I can say exactly what I mean, you can understand exactly what I meant, and I can be sure you have understood it exactly? Many people have tried to answer these questions, so let's go on a mathematical tour through universal languages and the incomplete search for linguistic perfection.

The crucial point is that knowing this [perfect] language would be like having a key to universal knowledge. If you’re a theologian, it would bring you closer, very close, to God’s thoughts, which is dangerous. If you’re a magician, it would give you magical powers. If you’re a linguist, it would tell you the original, pure, uncorrupted language from which all languages descend.

How does this fit into Kernel?¶

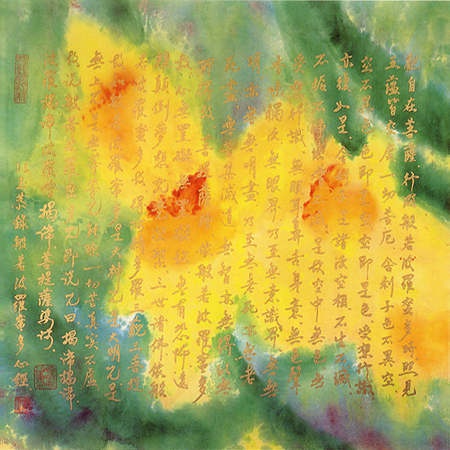

The sacred is not perfect. The source of what we call "sacred" is beyond any label, including "perfect". When we conflate the two, we propagate violent and oppressive ideologies which are convinced of their own correctness or truth. The sacred as we experience it in every day life is undecidable, irreducible, paradoxical.

When we accept this fact, as this article will show you, it reveals some really interesting and practical contexts in which we can more closely approach a perfection we know to be inherently irreducible. This is a truly beautiful thing to do. It is the best way to close this open-ended course. Thank you all, and we wish you a peace past any understanding.

Brief¶Gregory Chaitin begins his essay by discussing Umberto Eco's book The Search for the Perfect Language, and how it relates to some deep concepts in mathematics, coupled with a non-standard view on intellectual history. He starts by asking,

What is the perfect language? [... It is] the language whose structure directly expresses the structure of the world, in which concepts are expressed in their direct, original format.

He discusses some of the early figures of this search, including Raymond Lull and Gottfried Leibniz. Though both grounded in magical and theological thinking - as well as alchemy and hermeticism - it was Leibniz who first formulated the search in a modern way, calling this language the characteristica universalis. A crucial part of this language was something he called the calculus ratiocinator, by which we can reduce reasoning to calculation and thereby elide the need for opinionated arguments in favour of pure computation.

It was this notion which led him to develop calculus. Leibniz's version was slightly different from Newton's, in that his focus was specifically on the notation and formalism: how can we generate the most expressive power from the smallest set of meaningful symbols? His calculus presents a fundamentally mechanistic approach to proof, as he saw clearly the importance of having a formalism that led you automatically to the answer.

Prompt: A perfect language is one whose words directly express the original what?

Structure of the world.

Set and Setting¶

Chaitin then describes the theory of infinite sets as mathematical theology:

Cantor’s goal was to understand God. God is transcendent. The theory of infinite sets has a hierarchy of bigger and bigger infinities, the alephs, the ℵ’s, and so on.

These sets go on forever, as you can always make a new set out of the set of all previous sets, or by taking a union of all the members of an infinite sequence to get ever greater infinities. However, this leads to a contradiction, discovered by Bertrand Russell and now called the Russell paradox: if we take the universal set - the set of everything - and then consider the set of all subsets in it, then this set of all subsets must necessarily be bigger than the universal set. But how can this be? The set of all subsets of the universal set can neither be contain itself nor not contain itself - which poses a problem for mathematicians who are not theologically inclined.

While this contradiction never bothered Cantor - who took the view that it’s paradoxical for a finite being to try to comprehend a transcendent, infinite being, so paradoxes are fine - it led Russell to expose numerous contradictions in mathematical reasoning. As a response to this, another mathematician, David Hilbert, developed a formal axiomatic theory, which is a modern version of Leibniz’s characteristica universalis and calculus ratiocinator.

Axiomatic theories are written not in natural language, with its ambiguity and informal reasoning, but in precise, artificial languages based on mathematical logic which specifies the rules of the game precisely.

Empty In Completeness¶

The dream that there is a finite set of axioms which would allow us, in principle, to deduce all mathematical truth led to some truly beautiful work, in particular Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory and von Neumann integers.

Baruch Spinoza had a philosophical system in which the world is built out of only one substance, and that substance is God, that’s all there is. Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory is similar. Everything is sets, and every set is built out of the empty set. That’s all there is: the empty set, and sets built starting with the empty set.

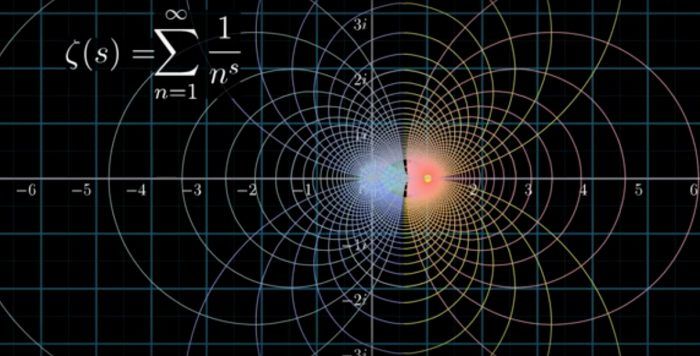

However, Gödel and Turing showed in the 1930's that you can’t have a perfect language or a formal axiomatic theory for all of mathematics because of 'incompleteness'. Gödel began with the statement "This statement is unprovable" and proceeded to show how the paradox at the heart of this (using Gödel numbering) reveals that we cannot capture all mathematical truth in any theory.

Turing derived incompleteness from a more fundamental phenomenon:

Turing’s insight in 1936 was that incompleteness, which Gödel found in 1931, for any formal axiomatic theory, comes from a deeper phenomenon, which is uncomputability. Incompleteness is an immediate corollary of uncomputability, a concept which does not appear in Gödel’s 1931 paper.

The fact that Gödel's incompleteness is a result of uncomputability suggests that, while there is no perfect mathematical language, there are perfect languages for certain computations.

What Turing discovered in 1936 is that there’s a kind of completeness called universality and that there are universal Turing machines and universal programming languages [... that is,] a language in which every possible algorithm can be written.

Prompt: What paradoxical statement did Gödel use to prove incompleteness?

This statement is unprovable.

Algorithms and Information¶

Chaitin goes on to describe his own work in Algorithmic Information Theory, which derives incompleteness from an extreme form of uncomputability, called algorithmic irreducibility. A deeper understanding of the mathematically irreducible information contained in the Halting Problem allows us to

pick out, from Turing’s universal languages, maximally expressive programming languages, which are maximally compact.

AIT is really about deducing the size of the smallest program required to calculate something, which allows us to create "better" notions of perfection, defined in terms of conciseness.

The most expressive languages are the ones with the smallest programs. This definition of complexity is dry and technical. But let me put this into medieval terminology, which is much more colorful. What we’re asking is, how many yes/no decisions did God have to make to create something?—which is obviously a rather basic question to ask, if you consider that God is calculating the universe [...] God will naturally use the most perfect, most powerful programming languages, when he creates the world, to build everything.

These most powerful programming languages can be expressed succinctly in AIT by considering a particular class of universal Turing machines U, and the most efficient ways for these machines to be universal. Chaitin describes some of the ways we have of calculating this, which extend more deeply in the details of AIT than this brief will go.

What's most relevant is how we can define programs in self-delimiting ways. That is, how can we get our universal Turing machine U to know when a program has ended without adding an extra symbol (i.e. just using 0 and 1, no blanks); or extra information about the size of the program to the program itself, which would make any computation less concise than the ideal.

A self-delimiting program is one which knows when to stop. This is an elegant and simple idea which is rather difficult to understand in practice but, as always, close observation of the world around us should unearth some clues in surprising places. The video linked above reveals how deeper understanding of such phenomena suggest ever more succinct universal languages, but open the door to - for instance - regenerative abilities and new medicine.

Prompt: "Better" universal languages for computation are defined in terms of what linguistic feature?

Conciseness.

Just Write¶

These self-delimiting binary languages are the ones that the study of program-size complexity has led us to discriminate as the ideal languages, the most perfect languages. We got to them in two stages, 1960s AIT and 1970s AIT. These are languages for computation, for expressing algorithms, not for mathematical reasoning. They are universal programming languages that are maximally expressive, maximally concise.

What does this mean for the search for a perfect language? Well, it's a bit of a mixed bag. Hilbert's formal axiomatic theory—meant to establish all mathematical truth—is necessarily incomplete, and all formal reasoning has been proven to have a limit. However,

There are perfect languages for computing. We have universal Turing machines and universal programming languages, and although languages for reasoning cannot be complete, these universal programming languages are complete. Furthermore, AIT has picked out the most expressive programming languages, the ones that are particularly good to use for a theory of program-size complexity.

Practically speaking, the search for the perfect language has yielded some truly fascinating results. Theoretically, it has shown that mathematics contains infinite irreducible complexity and so there is no hope of finding a simple and elegant Theory of Everything like Hilbert imagined. That dream turned out to be a golem, but

from the perspective of the Middle Ages, I would say that the perfect languages that we’ve found have given us some magical, God-like power, which is that we can breathe life into some inanimate matter. Observe that hardware is analogous to the body, and software is analogous to the soul, and when you put software into a computer, this inanimate object comes to life and creates virtual worlds.

Importantly, such power is limited by both the imagination of the programmer and by physical reality: this web of correlated interactions. We may choose and work to accept with humour and love (i) our own limitations, (ii) the constraints of the environment within which we are embedded, and (iii) the affordances of our interfaces (those 'boundaries' between distinct yet coextensive bodies) with others. Only once we have sincerely engaged in this ongoing process can we begin to see clearly and with less hubris what it might mean to "assemble infinities out of finiteness".

On this note, it is worth spending some time with the poets before you go. T. S. Elliot once wrote:

"They constantly try to escape

From the darkness outside and within

By dreaming of systems so perfect that no one will need to be good.

But the man that is will shadow

The man that pretends to be."

This search for the perfect language is a beautiful one, but it is tempered always by the standard to which all language must be held: what Marianne Brün calls "the imagery of human desire". When undertaking this search, it might help us to ask what "breathtaking eloquence and simple terms" explain "what we, today, almost speechlessly have wanted so much".

My suggestion is that what we want is simply to be good. Happily, the language of the good is also a language of self-imposed limits, which seeks perfect expression only as a means towards realizing a convivial life lived together in the golden mean. This golden mean, or middle path, is akin to the game of least complexity, because it requires no additional symbol, only a kind of rhythmic harmony; a balance of the whole.